‘Tracer and Wedge’ is an exhibition spread through the L-shaped ground floor project space of Mirabel Studios (Manchester, UK) populated with wall based art work, all responding to 'painting' as a broad thematic.

All artists involved have a historical or active relationship with Manchester art, often going back decades, and this shows in the focus and refinement within their practices; a kind of radical conservatism which seems oddly refreshing.

The relatively small scale of the works exhibited demands an enforced intimacy between viewer and work. An intimacy unconcerned with the surrounding architecture; except as a vertical support for the isolated sparring between surface and eye.

There is also an added complication, the works tend to allude to the act of using painting as a way of momentarily holding static the act of transcription between artistic forms.

As an introductory example, David Alker's 'The Seventeenth Century Landscape' sequence of five miniature paintings - most about 8 cm square - are transcriptions of photographs of a 1920s diorama of the construction of a large seventeenth century wooden ship. With titles sounding like chapters from Moby Dick ('The Hull', 'Capstan', The Ferry', etc) the horizontal line of representational paintings of the act of construction imply a narrative progression without a promise of chronological veracity.

Rick Copsey's 'Paintscapes' also uses a reduced scale - here all 20 cm square - in a horizontal display of stormy colour-tinted c-type prints of gothic seascapes. They are, in fact, microscopic photographs of paint palettes vastly enlarged. Another frustratingly layered act of transcription.

The relatively simple still life format of Rebecca Sitar's slightly larger oil paintings 'Untitled (Grey In Pink)', 'Pods' and 'Kernel' momentarily trick a viewer with a stabilizing familiarity but quickly reveal themselves to be equally destabilizing in the readability stakes: 'Untitled (Grey In Pink)' could be a rocky island sat on top of a pale wash of pink over grey or a ragged shape cut in the surface wash. 'Pods' seem to be constructing themselves from the space around them and, best of all, 'Kernel' is an ill-defined shape sat in a seductively deep purple black.

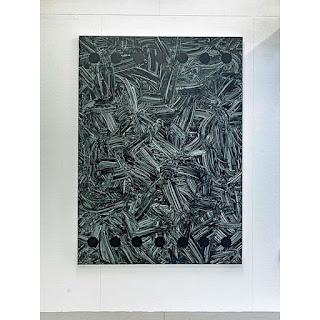

In stylistic opposition are Nick Jordan's domestic scale oil paintings 'California Typewriter' and 'Documentary Sounds'.

Both have the strong graphic clarity of Pop Art; both appear to have been transplanted from a European art exhibition set some time in the 1960s.

The most demandingly enigmatic pieces are Samantha Donnelly's framed c-type prints which look like collages with fragments of figures, studio shots and suggestive explanatory text - all indicating a magazine article about an artist and their work.

So within 'Tracer and Wedge' the containing rectangle of a picture surface can act as a platform for material play, an impossible spatial conundrum, or an idiosyncratic dissection and re-staging of historical models for fixing visual information.

So, microscopically small areas of paint palettes can transmute into gothic seascapes; severe formal signage allude to senses other than the optical; archaic dioramas can be unpicked and restaged as storyboarded narratives of the paintings own construction, whilst spartan still lifes start to drift away from a painterly and descriptive legibility.

However, edited from the chaos of the real world, all act as a temporary congealing of the movement of thought into a stubbornly solid object event; all allude to actions and forces which escape the controlling stamp of visibility.