Joe Devlin’s work has historically centred on copying, transcribing or somehow reusing the stains, interventions and scribbled marginalia that borrowers have left peppering the pages of library books.

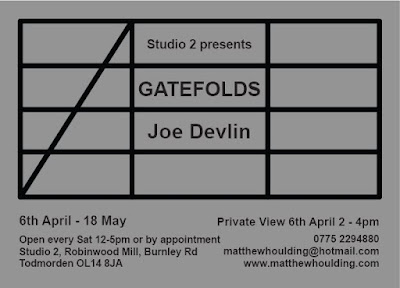

His Todmorden-based exhibition ‘Gatefolds’ is at a slight variance from his usual productive theft. Here Devlin has lifted a page of simple line drawings recording the different structural designs of farm gates, probably from a 1930s book. All twelve designs have bold no nonsense regional names: ‘Pembroke’, ‘Montgomery’, ‘Cumberland’, and so on.

Devlin’s page compiling these appropriated reductive drawings are blankly neutral presentations indicating these hinged structures; hard delineations of the operationally active which are themselves mechanical reactions to any compulsion to expressively map with the tools of drawing.

Acting as retreating markers between the mucky black sky-mirroring puddles, the crusting cow-pats, the bumps and contours which coat rough horizontal rectangles of field and ground; the organizing frameworks of gates map the pastoral landscape.

The thick black lines framing blocks of white paper suggest drably functional pieces of landscape furniture, ones designed to either regulate, or at least to slow the pace of, independent movement But they also act as guides for the viewing eye to trace the hermetically sealed linear structures bounded by its framing horizontal oblong format.

In a further act of physical transcription the linear designs have been re-presented as small aluminium-silver freestanding, shelf-bound sculptural works. Miniature Modernist inflected rectangles with the beginnings of gentle, Origami folds dictated by the vertical and diagonal lines of the source diagrams which have then been photographed, the photographs layered in a pile in the corner of the studio. A potential book-in-waiting.

A simplistic reading of the show could assume that the territorial musings of a confused mid-Brexit UK are somehow being alluded to by an ‘appropriation’ of regional variations in directive field furniture. This is, however, an intentional comedic act of misdirection.

The real substance of the exercise is both much simpler and considerably more complex. The literalness of the lurching moments of transcription folds back on themselves, from deformation of the authority of the original taxonomy of regional gates to their productive reimaginings as ‘art-objects’ which then, via photography, head back to the flat universe of images and their inevitable supporting text.

Even if they detour through rigid and legible formal structurings - the written word, sculptures shapes and depths, photography’s ‘indexicality’ and digital shiftiness - the meandering and interweaving functions of author, reader, viewer and producer are the actual constants. The assumed authority of an originating authorship is the slyly targeted centre of the artist’s criticism, even if this includes undermining the primary importance of artists themselves in the whole interpretive game.